I first heard of Vanessa Place and Les Figues in a cab going from JFK to midtown. I was with fellow poet Christan Bok who had much to say about Place, the press, and the upcoming n/oulipo publication (a compendium of the noulipo conference). Then I saw the novel and was smitten. You’ll find a mini-review of it here, alongside Marie-Claire Blais, but I repost some of it by way of an introduction to the interview that follows.

I first heard of Vanessa Place and Les Figues in a cab going from JFK to midtown. I was with fellow poet Christan Bok who had much to say about Place, the press, and the upcoming n/oulipo publication (a compendium of the noulipo conference). Then I saw the novel and was smitten. You’ll find a mini-review of it here, alongside Marie-Claire Blais, but I repost some of it by way of an introduction to the interview that follows.

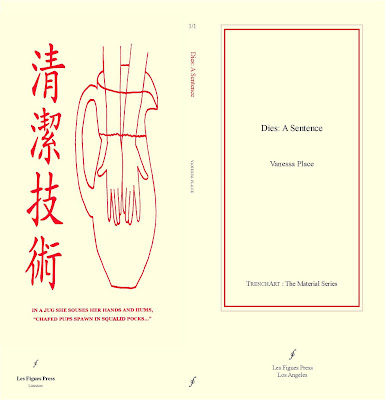

Relative newcomer Vanessa Place, a criminal appellate attorney and co-founder of the magnificent Les Figues Press, offers a 50,000 word, one-sentence novel set in World War I, and often right in the trenches of it. Circumnavigating, diverging, listing, relishing in the feast of language on so many levels…it comes out, as Stein says, and after a while it doesn’t have to come out ugly. This is the price paid for all the experimenting…our “crisis jubilee”….

Dies: A Sentence is a thing of beauty right from the beginning:

The maw that rends without tearing, the maggoty claw that serves you, what, my baby buttercup, prunes stewed softly in their own juices or a good slap in the face, there’s no accounting for history in any event, even such a one as this one, O, we’re knee-deep in this one, you and me, we’re practically puppets, making all sorts of fingers dance above us, what do you say, shall we give it another whirl, we can go naked, I suppose, there’s nothing to stop us and everything points in that direction, do you think there will be much music later and of what variety, we’ve that, at least, now that there’s nothing left, though there’s plenty of pieces to be gathered by the wool-coated orphans and their musty mums, they’ll put us in warm wicker baskets, cover us with a cozy blanket of snow, and carry us home…

Difficult to excerpt, but my experience with it so far is really one of waves, small, very distinct movements that blend one into the other. And the language! Check this out:

there was sausage in my veins and roast pork beneath my feet, what’s worst you say, you callous bastard, how can you squat there armlessly stirring a pot of camp stew and feign sudden irony, it’ll get you nowhere, you know, that bit of levity one wears like a rubber nose in the face of cold terror, such weak crooked lenitive proves a man’s uncrutch…

Not since The Waves have I been compelled to read an experimental novel through. Not just to appreciate the concept but to actually read it through…and I am still reading and thinking about what makes conceptual fiction work. And why this one seems to work so well. I’ve made it through to the end, but only because I had to for the sake of discussion. I’m going through again, and it’s a slow, sensual pleasure and a much deserved break from various essays on the boil. Vanessa Place agreed to talk to me via email. Due to time constraints our conversation has taken place over weeks and it isn’t finished either. I offer you round one.

LH: Vanessa, from what I can gather, Dies is your first published novel, but surely you have written fiction before that?

VP: This suggests Dies is fiction, which suggests interesting issues of form and institutional critique. The shortish answer is I had been working on a large project (La Medusa) and wrote Dies between drafts. I spent about 10 years writing Medusa; the first draft of Dies was written in about three months sometime around year four. I then put Dies away, and returned to the bigger monster. I did write a few odds and ends along the way, pieces published as everything from experimental nonfiction to straight poetry, but no sustained work. After finishing my final draft of Medusa, I took Dies out and polished it for Les Figues. Happily, Fiction Collective 2 is publishing Medusa this August.

LH: I should have said “prose” rather than fiction. Is your resistance one of genre, or form?

VP: I have no resistance to form, which would be like having a resistance to red clay, or lead white. Genre’s the thing, foolish thing, oddly stubborn. The most avant-seeming people ask you straight-faced if you are a poet or a fiction writer. I find yes is a very good answer. It reassures the questioner, without solving the question. Rather like answering whether someone is guilty or innocent.

LH: Where did the idea for Dies come from? Was it an idea that morphed, or a project that you proposed and then fulfilled?

VP: Dies was contrapuntal. As noted, I had been working on a very big project composed of very many fragments for a very long time, and wanted a palate-cleanser. The plate-spinning of the larger work immediately suggested its opposite: a single form that falls constantly, though incompletely, apart. The sentence is the basic formal unit of prose, counted as the container of thought. Shortly thereafter, I saw a photograph of a WWI soldier crossing a field who had gotten a leg snagged in some wire, and wondered what it would be like to be suspended in that wait, anticipating the bullet or blast that you cannot escape but can only attempt to negotiate. Death marks, or punctuates, the basic formal unit of human existence; death is the basic human sentence. The formal question becomes how to kill the sentence, how to grope pathetically towards “Death, once dead there’s no more dying then.”

LH: The torn leg is one of the tropes that leads us through the text. It’s a powerful image, and speaks to the obvious disconnect of war and carnage, but also to our investment in compartmentalization I think. Was that something you were thinking about?

VP: Fragments, I suppose, are always on the mind. They can be a bit of a cheat as they too easily serve as synecdoche, but are not a cheat in that they also incant the missing, playing the positive role of negative space. Compartmentalization is a gorgeous device for feigning wholeness, just as warrens create the illusion of connection and at least the potential for movement. Stew is good for food.

LH: “Death marks, or punctuates, the basic formal unit of human existence; death is the basic human sentence…” This is intriguing, and certainly forces one to think of text literally as body. I’m thinking too of Stein’s bumpy ride through the first world war, which one feels here. As one feels the resistance to closure. A resistance that becomes emblematic of a desire to live. Which leads me to ask, is this found text?

VP: That’s a wonderful question; I wish it were, or I wish I’d thought of incorporating found elements within its folds. But aside from the Hugh MacDiarmid poem near the beginning of the book, it’s all my creation. That makes me slavish to that same desire, I think.

LH: I am astounded at the deft way you shift in and out of consciousness. I’m working through the novel and I keep being distracted by my desire to pinpoint transitions. They are so seamless. How did you do that?

VP: I like to listen while I’m talking.

LH: Recently I watched Atonement, which I wasn’t intending to, and to my surprise I found the movie intriguing, particularly the war scenes in which Robbie finds himself wandering in a kind of carnivalesque masquerade. I come back to this notion of literalization, which I’m trying to work through—it comes from Marjorie Perloff and has been a site of interrogation recently by Jennifer Ashton. In any case, your novel takes us through many consciousnesses, which all seem convincing, the language, the cadence of mind but also very tangibly body. Perhaps this is why I was so convinced the text was found. It seemed like a time capsule of this moment. Then the contemporary references started to crop up etc. Is there something about the body and consciousness you wanted to say in particular?

VP: I think I say it more directly in La Medusa, and said so again in my paper for the Conceptual Poetry conference that Marjorie Perloff sponsored: we are embodied in a post-Cartesian sense. There is no split between consciousness and the sack of skin it comes in. Kenny Goldsmith’s nice mention of my paper in Harriet misses precisely this point, as the paper included not only tampon insertion instructions, but an Army marching song and a Yeats poem. Language may be found roaming about or Romanticized, but always falls with an orific splat.

LH: There are several sequences I want to speak of, the Time for one: “Time took a foil from its throat, well, I can’t answer that now can I…” (49). In her introduction to the novel Susan McCabe points out that time is animated here, and further that “hanging over it all is the despondency of the future conditional.” Perhaps this gets at the immediacy of the text, a kind of avant-terrorism (in McCabe’s words) that illuminates as it interrogates the constant creative force of thinking/remembering. It feels very reorienting, and I wonder if that is partly your intention.

VP: Constant reorientation. English is a wonderful bastard tongue, but comes up short in its verb tenses; to remedy this, I gave the future conditional a personality (like Time has its high-heeled personae), and then resorted to enjambing tenses. Time being physically reconstituted space, the enjambment forces a constant shuffle between history and geography, until, with any luck at all, there’s no divide between the two – just like real life. It’s very mimetic in that way.

LH: As you know I’m a big fan of Beckett. Could he have been a figure in Dies?

VP: He could have been its wet-nurse.

LH: I’m marveling at the language, which I’m still surprised to find isn’t found. Your text has the energy, the enjambed imagery of a found and/or sculpted text—flarf or recombined. You talk about reorientation—and yes, it is, but strangely so given the compact and often startling word combinations. It’s like oral/aural crack: “chill and cannonade,” “tinted an ill-augur’d pink,” “our bailiff will gladly comb you for nits and eggs of hate” (40), “we marveled at the knacked welter of our biceps” (66), hard to choose from so many on every page! And then there is the imagery, not just the sound: ”each cage thickly trophied with these thin and brittle scalps” (74), “he tied a length of silk to one of the sparrow’s legs” (13), “a golden turtle with alabaster mail, a mutton-mouthed lion with candlestick paws” (104). Are you a collector of sounds? Is this beadwork? Is this a Panopticon of perspective?

VP: Sounds, yes, not so much collected as petted as they trip through the pats of text. That’s what’s so ineffably lovely about writing, you know, the meat and musical motion of the thing. These examples you’ve picked are nice in that you call them oral while they are aural and textual, and still, I aim for language that begs to be put in the mouth. And I do love the panopticon, almost as much as I love the eyes of flies. But beads are a bother.

LH: “…for it’s a plain truth that color trivializes life…”(30). I loved this section—which goes from grays to granite to pale fingers a “lacquered pumice,” to a meditation on time—one of many—or Hannah Arendt navigating LA freeways?

VP: I want writing that’s so thick with sound and sense that you can see right through it to the pent little hearts within. We are a terrible and puny species. Don’t you think tatting is our grace?

from Dies:

all unhappy families are identical as apricots, and all men idem,

and the stone-centered quiddity of our suffering is what puts the

bread on the butter or the butter on the bread, it’s all very sad,

this bread and butter business, it’s as if we’ve given up dancing

altogether and although I find myself temporarily legless, I keep

my hops up, never say die, that’s what I say, not while there’s

still another limb of lamb, for that’s what hope dines on, and

there is hope, sure as bread pudding, you see how I retreated

there, I saw you wince at the coming shot and so I

recharacterized, I can, you know, nothing’s written in stone, or it

is, but we’re penciled in at best, we’re a sketch-book of emphatic

caprices, a homespun comfort for the quilted set, those happy

many, who damn violence with but a single hand, brightly

ribboned at the wrist, still, a passing paraphilia made Time tarry,

the two struck up an argument on the pleasures of sheet music,

for which the spoiled beauty was a heartless advocate, but Time

sneezed, categorically dismissing the whole encounter as

hoarding and wasting, what was the point, Time clucked, of

keeping track of a tock, it’s a schoolboy’s trick to note the

passing minutia, and the lady, whose nails were bitten to the

quick but to no end, begged to disagree, she said such sweet

sounds were in themselves sweetly spent, whereupon Time

puffed its bejeweled breast and bragged there was no knell that

wouldn’t lisp under his authority, but Time’s rude boast was

duly altered by me, yes, you too, Juan, you’re a genius, don’t let

them tell you any different, well, let’s be honest, we’re both

geniuses, we have that at least, that’ll give us some comfort in

the early fileted light, we’ll go out in a blaze of particulate glory,

I imagine, with an éclat of fat and a frenzy of mythomania,

More to come on Dies, and the upcoming Medusa.

Comments are closed.