This “interview” is the first in a series of dialogues between Les Figues authors and invited interlocutors. Departing from the q/a format, we encourage digressions and dialogue across lines, space, and membranes. As the Kathy Acker Fellow and curator of the Les Figues blog, I was interested in curating alternative documents of poetic collaboration and investigation. This dialogue between Pablo Lopez and derek beaulieu on his book Kern occurred over a series of emails, and over a few weeks. We’ve given you the best lines. – Margaret Rhee

Pablo Lopez: The poems in Kern exist within a rigorously limited field of composition, within that field you have negated a number of linguistic modalities that have formidable and important traditions as it relates to poetry. Considering those negations, I’m most interested in your decision to dispense with syntax and lineation.

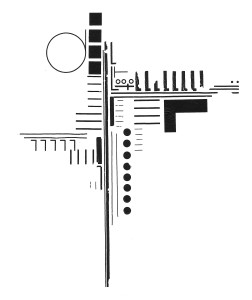

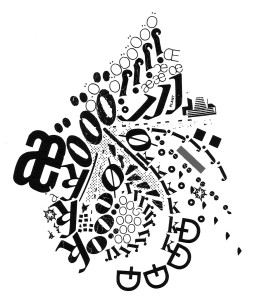

derek beaulieu: Lineation, syntax, metrics (etc) aren’t present in these poems because they don’t follow a poetic tradition that has needed them. Concrete poetry historically has rejected traditional poetics in favour of form that is closer to advertising slogans and way-finding logos. Kern rejects the traditional poetic as being insufficiently equipped to adequately reflect the reading and writing habits of a contemporary landscape.

Lopez: In a sense these poems are highly strategic in their compositional makeup, and yet they are transgressive in that they do not abide by the familiar protocols of legibility. What, then, is the role of transgressivity as it operates in this collection and locally in each poem?

beaulieu: Kern embraces the legibility of street-signs and logos—which operates differently from literary legibility; it’s a legibility of looking rather than reading. Even at its most decayed and rusted, we can still recognize a Coca-Cola logo as pointing to a product—we still identify the content based on the smallest fragments of the “look.” With Kern, and recognizing the work of designers and poets in the ‘50s and ‘60s such as Mary Ellen Solt, Eugen Gomringer and the de Campos Brothers, I embrace the logoization of language as a means of generating a new poetry.

Lopez: Yes, clearly the poems in Kern operate in the concrete tradition, simultaneously it seems that they maintain a particular ambition beyond the parameters of that category. Does that ring true in your estimation? Also, I find it telling that in your embrace of the ‘logoization’ of language you pay heed to the role of the new, ‘generating new poetry,’ as you put it. It calls to mind moments in Benjamin, where he refers to Baudelaire’s disinterest in progress while remaining inclined toward the pursuit of newness. Kern seems to be a similar case, offering a stripe of ‘new poetry’ that looks to historical novelty in the shape of concrete poetry rather than fashioning gimcrack forms for its own sake. There’s no apparent romance for the avant-garde either, but rather an attempt to specify one’s own poetics through the act of writing against the grain of a number of literary protocols.

beaulieu: I agree that the poems in Kern strive beyond the boundaries of the poetic, for sure. Certainly the work by my peers which intrigues me the most is the work that I have difficulty recognizing as poetry at all—the work that looks more like graphic design, data presentation, signage, scientific results … or even quotidian language, language which reframes the everyday (the everyday, though not “normal,” nor “uninteresting”). Progress is entwined with capitalism, sure … I think the idea of poetry as a tool of change, or a tool for progress is testing its limit-case. I mean, poetry—as it stands—is emptied of power and audience, it’s no longer an engine for social change. I’m more interested in poetry that doesn’t attempt to “say” or “mean” or “change” but instead lumpishly stands in the way, unreadable, un-moveable, indigestible but uncomfortably familiar.

beaulieu: I agree that the poems in Kern strive beyond the boundaries of the poetic, for sure. Certainly the work by my peers which intrigues me the most is the work that I have difficulty recognizing as poetry at all—the work that looks more like graphic design, data presentation, signage, scientific results … or even quotidian language, language which reframes the everyday (the everyday, though not “normal,” nor “uninteresting”). Progress is entwined with capitalism, sure … I think the idea of poetry as a tool of change, or a tool for progress is testing its limit-case. I mean, poetry—as it stands—is emptied of power and audience, it’s no longer an engine for social change. I’m more interested in poetry that doesn’t attempt to “say” or “mean” or “change” but instead lumpishly stands in the way, unreadable, un-moveable, indigestible but uncomfortably familiar.

Lopez: Yes, works that resist initial legibility can offer important alternatives to prevailing orthodoxies, and apply a number of productive pressures—I mean this from an intellectual and creative standpoint, which to my mind, is both practical and political in its very orientation—both against the canonical purview of contemporary poetry as well as to preconceived notions of the experimental (I think I glean a similar sense from your use of scare quotes around ‘normal’ and ‘uninteresting’ writing). It seems that the creative density and mass of experimentalism is diminished as soon as it becomes identifiable enough to become parlance and easily legible, as you suggest. I suppose Kern is a mode of response in this way, as well as being a productive departure. For me there’s a certain amount of active uncertainty involved in these pieces. Not only in the actual writing of them, if that was in fact the case, but also in that they openly express uncertainty, uncertainty as a mode and form of knowledge. This seems to be an example of ‘standing in the way’ as you put it. I’m interested in this notion, perhaps you could elaborate on this practice of standing in the way. I can’t help but understand it as a generative practice.

beaulieu: Canadian poet bpNichol playfully states “[a]ll that signifies can be sold” and Sianne Ngai vehemently argues “most forms of cultural subversion are ultimately contained.” These poems thwart close reading as they don’t work along expected signifying chains; they “won’t coagulate into a unitary meaning and it also won’t move; it can’t be displaced” (to quote Ngai). It is precisely this resistance to displacement and refusal to co-operate that excites me: a poetry that co-opts degenerated text, letteral fragmentation, palimpsestic text and waste as poetic tropes. Concrete poetry’s resistance to reading, and close-reading in particular, foregrounds the materiality of language, the rubble with which poets are left after the commercialization and co-opting of poetry and poetics for marketing, sales and government. Concrete rejects the spoken in favour of the written, and then rejects the legible in favour of the illegible. Instead of trying to reclaim poetry as generative, Concrete sits there, unwilling to participate, unwilling to mean, unwilling to do anything other than simply take up space. Vito Acconci postulates that poetry can “use language to cover a space rather than discover a meaning”, I am drawn to the thought of a poetry which refuses to be poetic and does everything it can to use the semantic “tools” of poetry in a way which “bear[s] witness to its creator’s articulate expression of his or her own inarticulateness, or to his or her potential to not-express, or not be articulate.” (again quoting Ngai). Concrete poetry lays bare the myth of transparency. Instead of the page operating as a smooth medium for clear, emotional transference, it is the site of a lump, a wad, a knot of immovable refuse. Concrete poetry rejects McCaffery’s “valorization of the representational” in favour of a hairball of indigestible matter.

Lopez: Thinking in these terms puts Kern in conversation with some of the great works of refusal, John Cage comes to mind, as does Celan (please pardon the arbitrariness of these associations!) but for obviously different reasons. Both mobilized various modes of illegibility in profoundly affective ways: Cage in his commitment to inclusion where composition was concerned, and Celan with his determined use of syllogisms and reticence. I see a number of similarities where your work is concerned.

Also, the fact that you mention Acconci calls further attention to the similarities between the poems in Kern and the visual arts. Oddly enough, or perhaps more to the point, is that Acconci’s an artist that made art but no real art objects, in this way it’s viable to situate Acconci into a reading where art, like the poems in Kern, ‘cover a space rather than discover meaning’—Bifo Berardi adds to this notion with the idea that poetic language occupies the specific space of communication, and when successful in that occupation, renders it non-exchangeable. In such a schema, Kern operates with a double sense in that it participates as both poetry and a visual art object—the significant difference is that in poetry Kern actively impedes, as we’ve been discussing, and yet in the field of visual, plastic, and spatial arts, it participates more seamlessly—is that at all a concern of yours? And how do you then consider the purely visual ramifications of your poems—and do you work to ensure that not only do they impede productively as poetry but that they participate and work compositionally in the field of the purely visual?

beaulieu: My friend Christian Bök jokes that the reason why writing fails in a gallery setting is that people don’t like to read standing up. Text art seems to try and mix reading habits (slow sustained focus on a book or article, usually in a seated position) with looking habits (quick glancing, browsing, scanning in a standing position) that work to the detriment of textuality. I would rather attempt to create text that fully embraces standing up (ha-ha), which operates both on a page and on a gallery wall. The poems in Kern are articulate in the history of visual poetry and textual poetry but integrate a realization that for poetry to most successful it must embrace looking at a visual field and therefore should be balanced and artful in execution.

beaulieu: My friend Christian Bök jokes that the reason why writing fails in a gallery setting is that people don’t like to read standing up. Text art seems to try and mix reading habits (slow sustained focus on a book or article, usually in a seated position) with looking habits (quick glancing, browsing, scanning in a standing position) that work to the detriment of textuality. I would rather attempt to create text that fully embraces standing up (ha-ha), which operates both on a page and on a gallery wall. The poems in Kern are articulate in the history of visual poetry and textual poetry but integrate a realization that for poetry to most successful it must embrace looking at a visual field and therefore should be balanced and artful in execution.

Lopez: Kern, and kerning, is a printing term but it also seems to play an active role in the composition of the poems in the collection as well as in your process as a poet. Perhaps you could delve into that a bit.

beaulieu: The title, Kern, is as you said, a printing term referring to adjusting the space between letters to improve readability; the tiny adjustments of letter-spacing. The poems in the book are basically exercises in kerning, adjusting the spacing—but instead of improving legibility, they trouble reading and lead the letters into uncertain areas. I also wanted the book itself to “kern” our expectations of form—to draw together the spaces between readability and visuality, between the poetic page and the gallery wall.

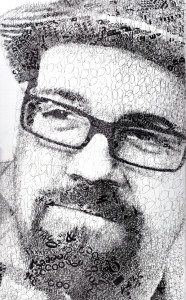

Dr. Derek Beaulieu is the author or editor of 16 books, the most recent of which are Please, No more poetry: the poetry of derek beaulieu (Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2013) and kern (Les Figues press, 2014). He is the publisher of the acclaimed no press and is the visual poetry editor at UBUWeb. Beaulieu has exhibited his work across Canada, the United States and Europe and is an award-winning instructor at the Alberta College of Art + Design. He is the 2014-2016 Poet Laureate of Calgary, Canada.

Dr. Derek Beaulieu is the author or editor of 16 books, the most recent of which are Please, No more poetry: the poetry of derek beaulieu (Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2013) and kern (Les Figues press, 2014). He is the publisher of the acclaimed no press and is the visual poetry editor at UBUWeb. Beaulieu has exhibited his work across Canada, the United States and Europe and is an award-winning instructor at the Alberta College of Art + Design. He is the 2014-2016 Poet Laureate of Calgary, Canada.

Pablo Lopez is the author of the NUMBERS (Called Back Books), and co-editor of an online journal (comma, poetry) that features innovative work in English and translation. He lives in Los Angeles.

Comments are closed.